60,000-year-old poison arrows from South Africa are the oldest poison weapons ever discovered

Five quartz arrowheads found in a South African cave were laced with a slow-acting tumbleweed poison that would have tired prey during long hunts.

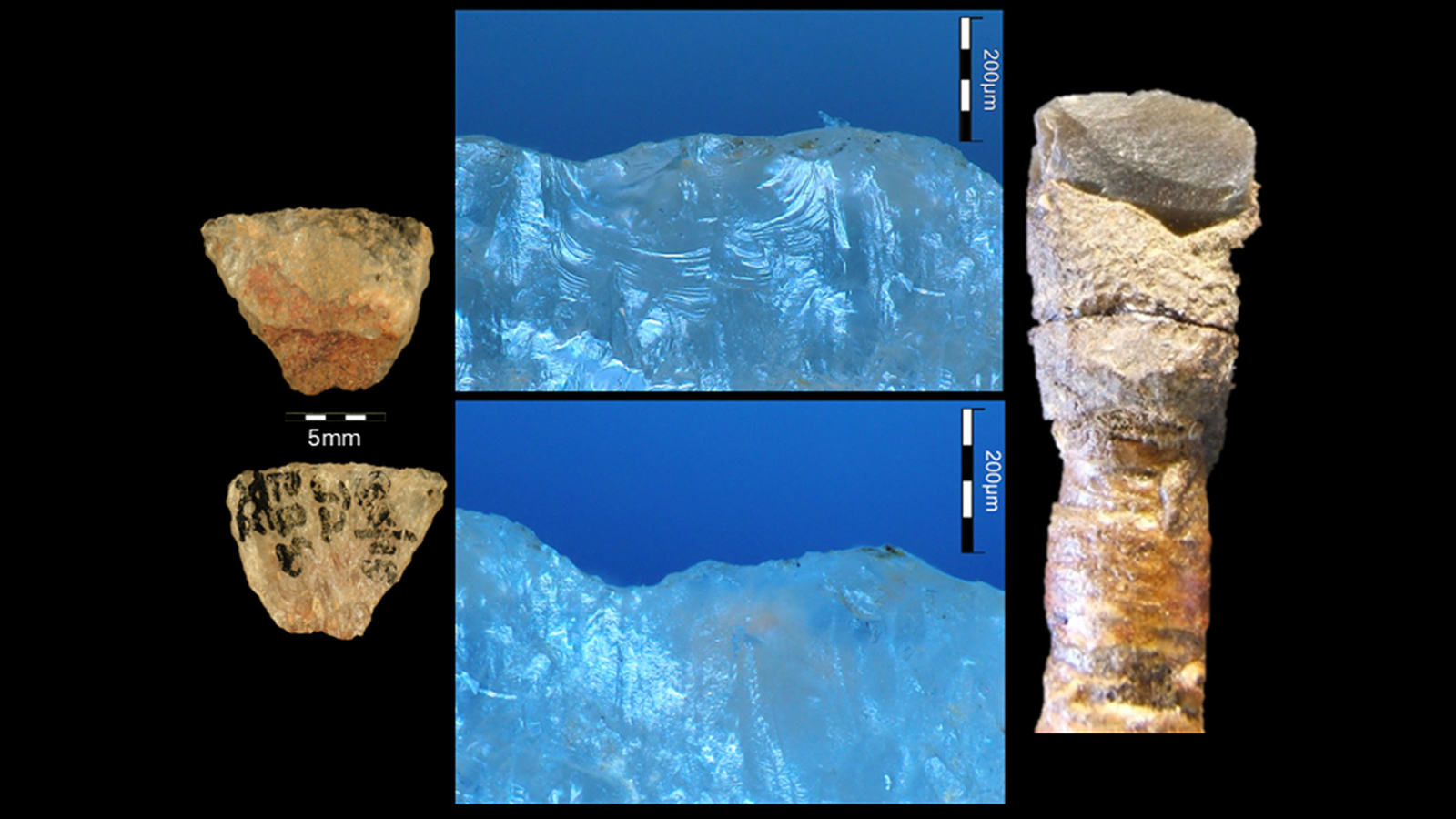

A closeup of the five arrowheads from Umhlatuzana rock shelter with two plant toxins. (Scale = 5 mm). The inset shows all 10 archaeological artifacts analyzed. (Image credit: Isaksson et al., Sci. Adv. 12, eadz3281)

A handful of 60,000-year-old arrow tips unearthed in a South African rock shelter are the oldest evidence of poison weapons in the world, a new study finds.

The discovery pushes back the confirmed use of poison weapons by hunter-gatherers by over 50,000 years.

The finding shows that prehistoric hunter-gatherers understood the pharmacological effects of these plants, the researchers said.

"Humans have long relied on plants for food and manufacturing tools, but this finding demonstrates the deliberate exploitation of plant biochemical properties," study lead author Sven Isaksson, a professor of laboratory archaeology at Stockholm University, told Live Science.

What's more, the poisoned arrow tips reveal that these prehistoric hunters could think in complex ways. The poison takes time to have an effect, so the hunters had to understand cause and effect and plan ahead for their hunts, Isaksson said.

Previously, the oldest unequivocal evidence for poison-weapon use was 7,000-year-old arrow poison tucked into the thigh bone of a hoofed mammal found in Kruger Cave in South Africa. Although there have been older findings — such as indirect evidence of a 24,000-year-old wooden "poison applicator" from Border Cave, also in South Africa — they are debated.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Poisoned weapons

Poisons degrade over time, but traces of these chemicals can survive in certain conditions.

The Umhlatuzana rock shelter, excavated in 1985, is one prime location for such conditions. Archaeologists had previously unearthed 649 crafted quartz fragments from the Howiesons Poort period, a distinct South African technological culture dating from 65,000 to 60,000 years ago. But no one had closely inspected the surfaces of these remnants, beyond looking for glues used to attach the arrow tips to the arrows' shafts.

For the new study, Isaksson and his team took a closer look at 10 of the 216 available arrowheads from an excavation layer dated to 60,000 years ago; these 10 were selected because they still had microscopic residue that could be analyzed.