First-ever 'superkilonova' double star explosion puzzles astronomers

A double explosion, in which a dying star split, then recombined, may be a long-hypothesized but never-before-seen "superkilonova."

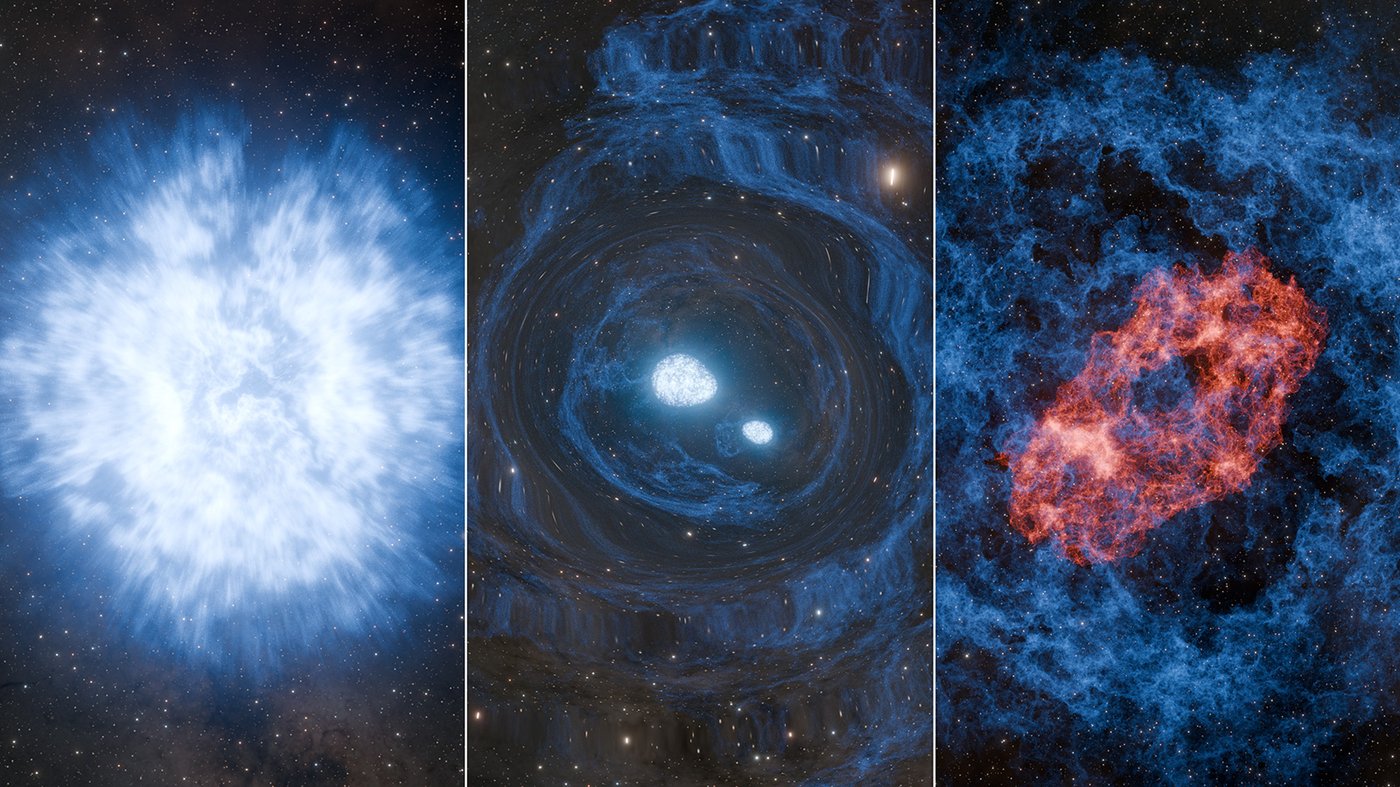

An artist's concept illustrates a never-before-seen superkilonova event. (Image credit: Caltech/K. Miller and R. Hurt (IPAC))

Scientists may have witnessed a massive, dying star split in two and then crash back together, triggering a never-before-seen double explosion. The explosion sent ripples through space-time and forged some of the universe's heaviest elements.

Most massive stars reach the ends of their lives by collapsing and exploding as supernovas, seeding the cosmos with elements such as carbon and iron. A different kind of cataclysm, known as a kilonova, occurs when the ultradense remnants of dead stars, called neutron stars, collide, forging even heavier elements like gold.

A two-in-one combo

AT2025ulz first caught astronomers' attention on Aug. 18, 2025, when gravitational wave detectors operated by the U.S.-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and its European partner, Virgo, registered a subtle signal consistent with the merger of two compact objects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Soon after, the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory in California spotted a rapidly fading red point of light in the same region of the sky, according to the statement. The event's behavior closely resembled that of GW170817 — the only confirmed kilonova, which was observed in 2017 — with its red glow consistent with freshly forged heavy elements such as gold and platinum.

Instead of fading as astronomers typically expect, AT2025ulz began to brighten again, the study reported. Follow-up observations from a dozen observatories around the world, including Hawaii's Keck Observatory, showed the light shifting toward bluer wavelengths and revealing fingerprints of hydrogen, a hallmark of a supernova rather than a kilonova.

RELATED STORIES

That data helped researchers confirm the presence of hydrogen and helium, indicating that the massive star had shed most of its hydrogen-rich outer layers before detonating, the paper noted.

To explain the baffling sequence, the team proposed that a massive, rapidly spinning star collapsed and exploded as a supernova. But instead of forming a single neutron star, its core split into two smaller neutron stars. Those newborn remnants then spiraled together and collided within hours, triggering a kilonova inside of the expanding debris of the supernova.