Jupiter ocean moon Europa likely lacks tectonic activity, reducing its chances for life

New models suggest that Europa has very little tectonic activity at its seafloor, which is potentially catastrophic news for the hopes of finding alien life within its ocean.

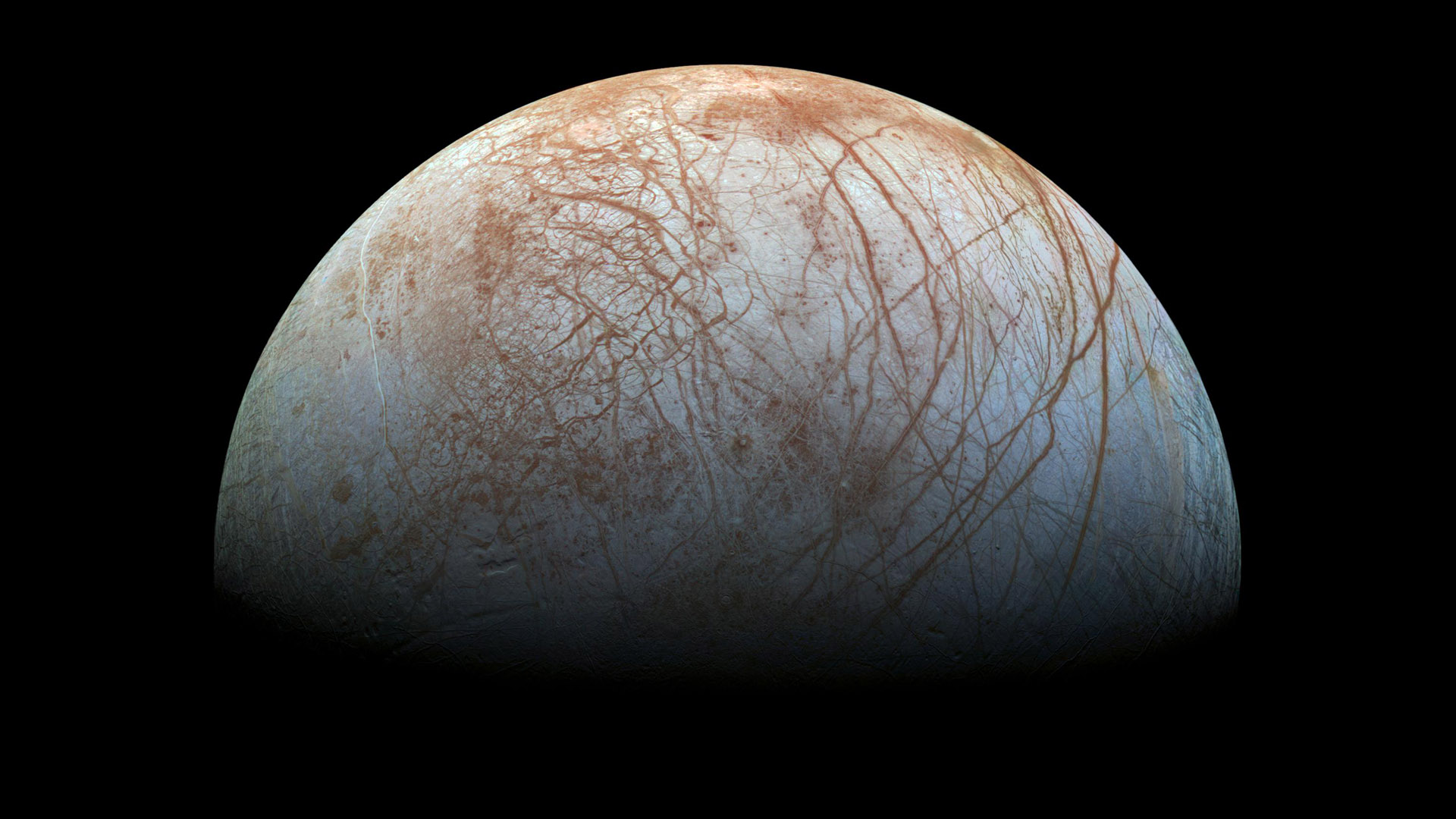

Jupiter's ocean moon Europa, as seen by NASA's Galileo probe. (Image credit: NASA)

Europa might not be the best place to look for alien life in the solar system after all.

A new study modeling what the floor of the Jupiter moon's hidden ocean is like concluded that tectonic activity — and the complex chemical reactions that such activity facilitates — is probably negligible.

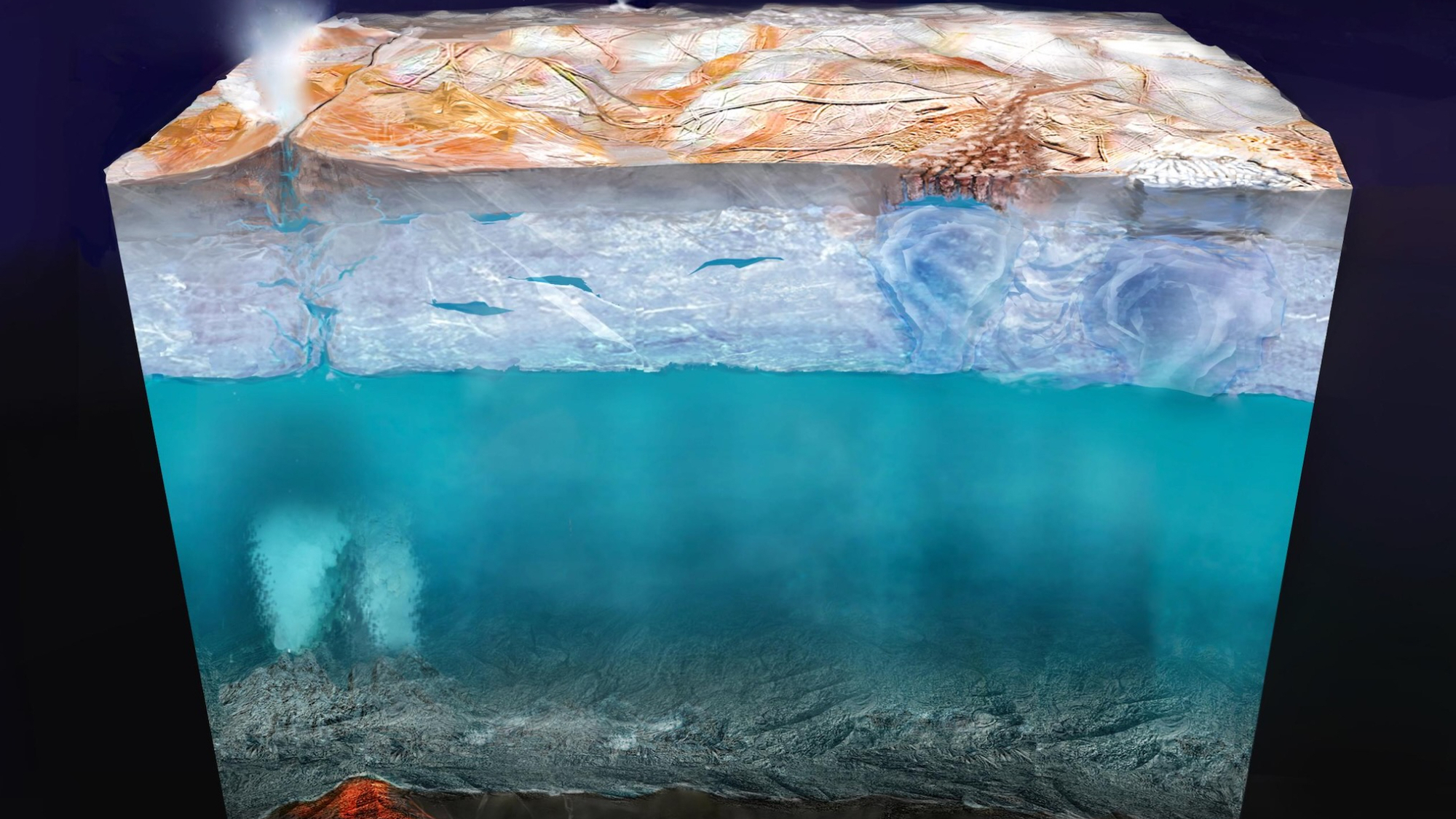

An artist's cross-section of Europa, showing the surface, the icy shell, the ocean and the sea floor. New modeling suggests that tectonic activity and hydrothermal vents might not be present. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Europa harbors a deep ocean beneath a shell of ice that's dozens of kilometers thick. This ocean wraps around a rocky core, but little is known about the interface between the ocean and the core. If life is to exist in Europa's ocean, it must somehow gain energy, most probably from interactions at the sea floor between water and rock. Access to fresh rock is vital in order to produce more nutrients.

On Earth, tectonic faulting in the seafloor enables water to plunge kilometers down into the rock, and as fresh faults are opened up by shifting tectonic plates, new rock is exposed, maintaining the nutrient supply released into the ocean through hydrothermal vents.

Byrne's team assessed the potential for tectonic activity on Europa's seafloor with a new model that factored in stresses from gravitational tides incurred by Jupiter, the long-term contraction of the moon as its interior gradually cools and the convection of heat energy through the mantle.

However, they found that none of these factors would be strong enough to produce tectonic activity. For example, tidal stresses occur because Europa's orbit around Jupiter is not perfectly circular but rather eccentric, in accordance with Johannes Kepler's first law of orbital motion. This means that, at certain points in each of its 84-hour orbits around Jupiter, Europa is closer to the planet than at other times, and the resulting gravitational differential leads to tides. However, for the tides to be strong enough to induce sufficient tectonic activity, the eccentricity of Europa's orbit would have to be greater — more elongated — than it is (an eccentricity of 0.441 compared to the actual value of 0.009). Even if repeated tidal stresses weaken the uppermost part of Europa's seafloor, creating shallow fractures, they aren't intense enough to extend those faults deep down to new rock.