'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

A new study reveals that nerve cells receive periodic infusions of mitochondria from neighboring cells — and this may point to a new way of treating nerve pain.

The powerhouses of cells, the mitochondria, may be key to protecting nerves from damage and dysfunction. (Image credit: Naeblys via Getty Images)

Supplying nerves with a fresh supply of mitochondria could curb chronic nerve pain, a new study hints.

The research, conducted with mouse cells, live mice, and human tissues, reveals a previously unsung role of mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells. It shows that support cells within the nervous system can ship mitochondria to the nerves that respond to pressure, temperature and pain. But problems with that shipping process can deplete the nerves' energy reserves, causing them to malfunction.

The new study, published Wednesday (Jan. 7) in the journal Nature, points to potential new ways of heading off that neuronal breakdown — and one strategy could involve transferring mitochondria directly into nerves.

Fresh mitochondria reduce pain

The research zoomed in on satellite glial cells, unique cells that physically wrap themselves around the "roots" of nerve cells located near the spinal cord. The bodies of these nerve cells cluster together near the spine, and from each cluster, bundles of long fibers extend to different parts of the body, from head to toe. The longest of these fiber bundles belong to the sciatic nerve, which measures just over 3 feet (1 meter) long.

The sheer length of the fibers poses a "real challenge," because for a nerve to function properly, mitochondria made in the nerve's root must travel down to the end of each fiber, and that in itself requires energy to do, Ji said. That raises a question of how nerves maintain this power-hungry supply chain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

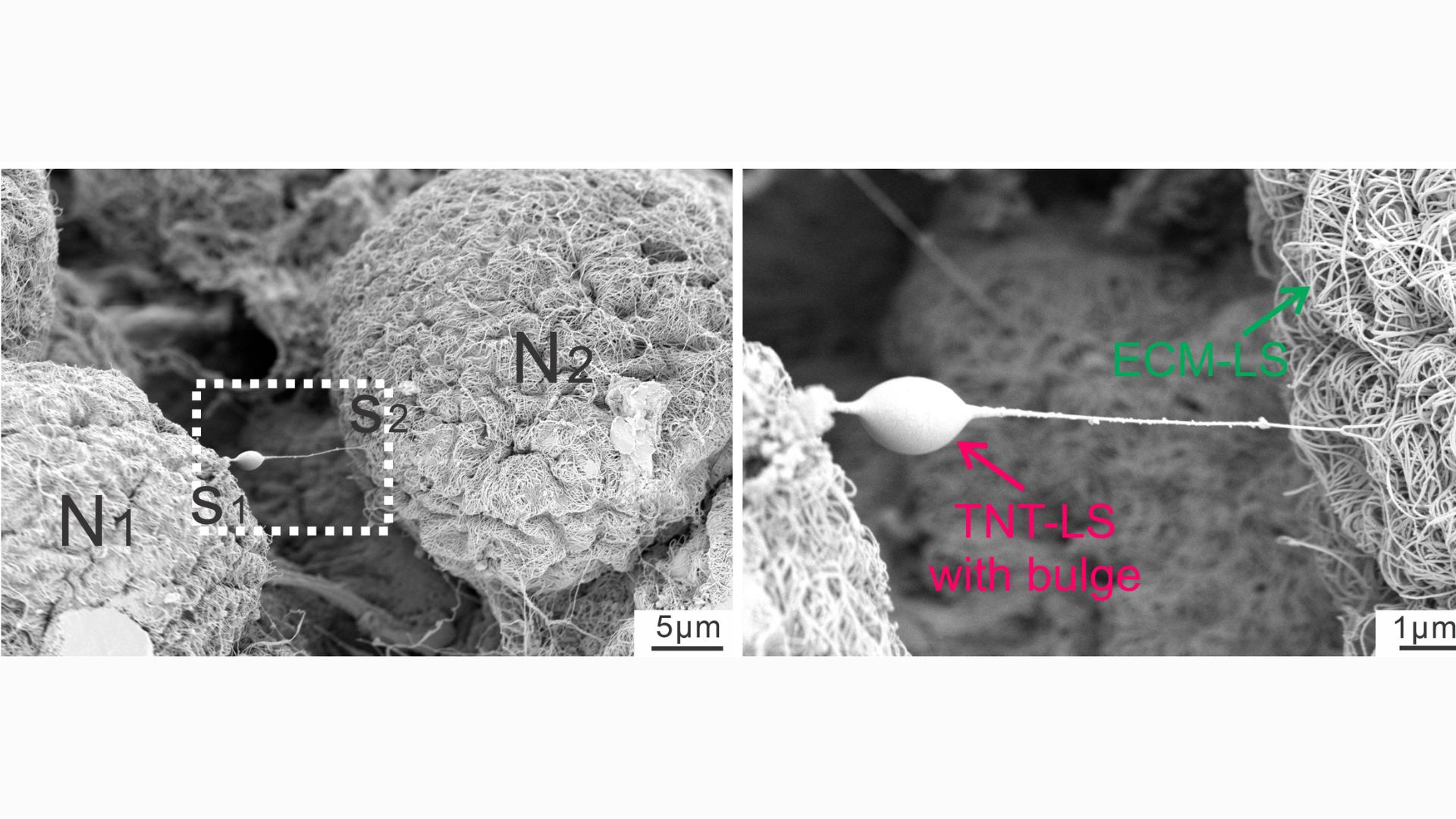

Scientists once thought that cells had to make all of their own mitochondria, but in recent years, they have uncovered evidence that cells swap mitochondria. This can occur between cells of the same type or between cells of different types, such as between a stem cell and an immune cell, for example. To facilitate the swap, cells construct tiny structures called tunneling nanotubes for the mitochondria to travel through, like spitballs sliding from one end of a straw to another.

Ji and his team wondered whether satellite glial cells might be able to send mitochondria to the nerve cells they encircle — and it turns out that they can.