Robots fashioned from dead lobster exoskeletons have awesome strength, light weight, and flexibility — necrobotics advance mixes sustainable food waste with synthetic components

Swiss scientists have demonstrated the use of dead lobster tails as robotic appendages.

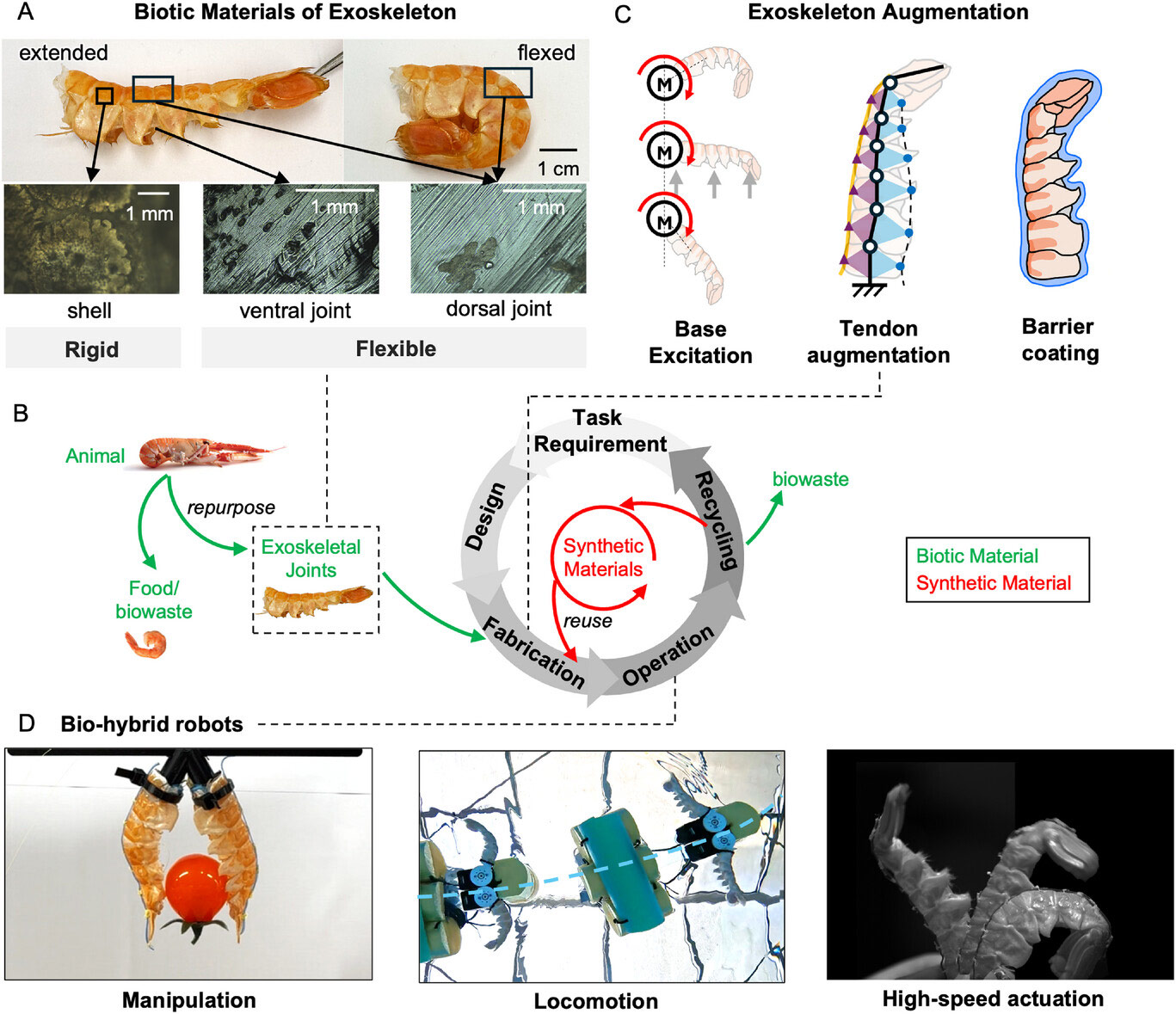

Swiss scientists have used dead lobster parts as robotic appendages. The strong yet flexible and lightweight exoskeletons of these marine animals have been successfully demonstrated as robotic manipulators, grippers, and swimmers or flappers flexing at up to 8 Hz. The use of dead animal parts makes this an advance in ‘necrobotics.’ This example of bio-hydrid robotics, from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), is particularly sustainable necro-tech, as it uses crustacean shells that are waste from food production.

"Dead Matter, Living Machines"

“Exoskeletons combine mineralized shells with joint membranes, providing a balance of rigidity and flexibility that allows their segments to move independently. These features enable crustaceans’ rapid, high-torque movements in water, but they can also be very useful for robotics,” explains EPFL’s CREATE Lab head Josie Hughes. “And by repurposing food waste, we propose a sustainable cyclic design process in which materials can be recycled and adapted for new tasks.”

In the video above, you can see a set of clips showing the scientists testing the dead crustacean exoskeleton’s use in robotics applications. Specifically, Langoustine tails are used as the robotic appendages throughout these tests. Langoustines are a smaller member of the lobster family, also known as Norway lobsters, Dublin Bay prawns, or scampi.

The first segment of the video shows a pair of these tails being used for gripping a variety of (mostly soft) objects. The associated research paper says that “a 3g exoskeleton [is] capable of supporting a 680g payload.” Though drastically outsized and outweighed by some of the objects, these necrobotic grippers are capable in lifting and manipulation, and don’t appear to easily damage things like tomatoes.

Later parts of the video show langoustine tails make for extremely capable robotic swimming appendages – no surprise. In air, the scientists found they could flap pretty fast, up to approx 8 Hz.

(Image credit: EPFL news blog)

Chitin, a natural biopolymer, is the key structural component in crustaceans (and insects), which makes their exoskeletons so useful here. It is a very easy to source materials, which is strong, flexible, and light weight, as well as being biodegradable and biocompatible.