School Employees' Lawsuit Claiming "Equity Training" Violated First Amendment Can Go Forward

So holds a majority of the Eighth Circuit federal court of appeals, sitting en banc.

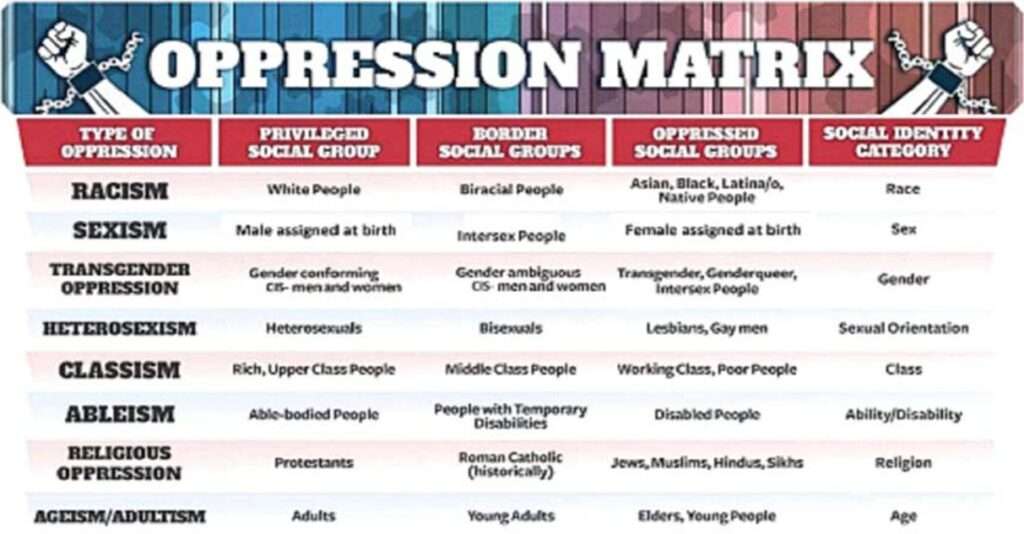

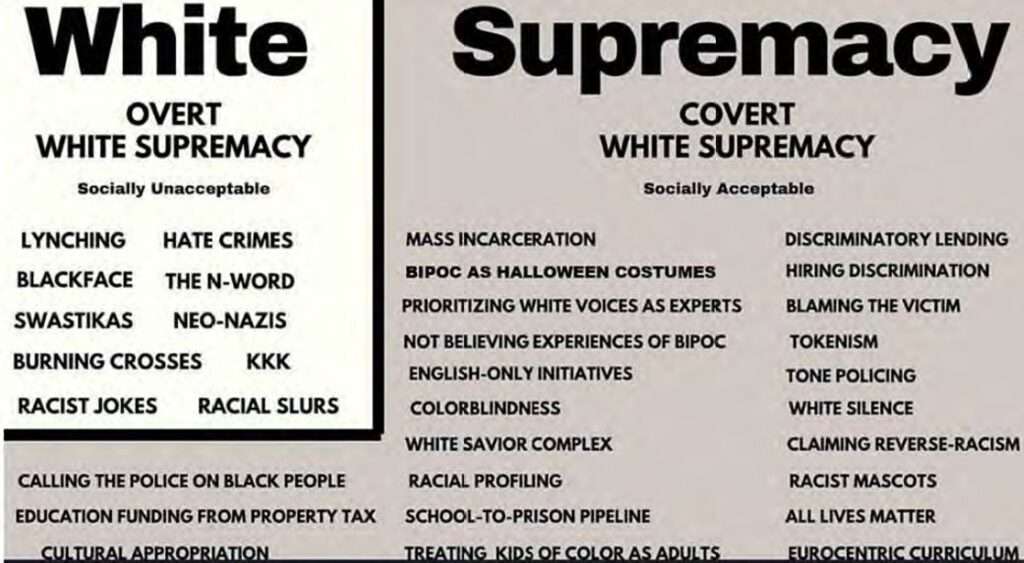

One of the images from the training, as reproduced in the majority opinion.

A short excerpt from Henderson v. Springfield R-12 School Dist., decided today by the Eighth Circuit Judge Ralph Erickson, joined by Judges Raymond Gruender, Duane Benton, David Stras, and Jonathan Kobes, and in large part by Judge Steven Grasz:

This is a challenging case involving the intersection of First Amendment principles with the advancement of the critical mission of understanding, educating, and creating an environment where all people, regardless of race, creed, or status are welcomed.

It is important to note at the outset what this case is not about. It is not about the ability of the school district to take issues regarding race and discrimination seriously or to educate students about those issues. It is not about, as claimed by the dissenters, whether telling employees to "be professional" amounts to a constitutional injury or whether a school district can enforce "basic expectations of every conversation in our society" without fear of a federal lawsuit. It is also not about whether we believe the views expressed by either party are appropriate or distasteful. It is not about an employer's ability to confirm employees understand the material being taught. Nor does it turn every personal belief held by an employee or a student that may be at odds with her employer or teacher into a federal cause of action.

It is about whether the plaintiffs have proffered sufficient evidence, when viewed in their favor, to show they suffered a concrete and particularized injury by being chilled from speaking during the training or by being compelled to speak due to a credible threat of an adverse consequence by the school district….

The court said the plaintiffs had indeed provided such evidence; for more on the facts related to that, see the full opinion. Here is an excerpt from the court's description of the training:

At the beginning of each [mandatory training] session, school district staff, including [plaintiffs] Lumley and Henderson, were provided several documents, including one entitled "Guiding Principles." The principles listed in this handout directed staff to "Stay Engaged," "Lean into your discomfort," "Speak YOUR Truth and from YOUR Lived Experiences," "Acknowledge YOUR privileges," "Seek to Understand," "Hold YOURSELF accountable," and "Be Professional." The "Guiding Principles" were repeated by the trainers early in the power point slide presentation. When the slide was published, the trainers explained to Henderson that she "needed to have 'courageous conversations;' that [she] must stay engaged; that the topics of the training can be uncomfortable, but [she] must 'lean into [her] discomfort;' that [she] should share [her] personal experiences and identities; and that [she] must acknowledge [her] privileges and hold [herself] accountable."

In addition to the comments made by the trainers, the power point slide contained an explicit warning that the plaintiffs took note of: "Be Professional — Or be Asked to Leave with No Credit." Also, during the introduction, the trainers told staff during the session Henderson attended that they "had to agree or [they] would lose credit and that [they] had to be an ally and it was part of [their] job duty to be an anti-racist educator." …

Henderson was required to complete seven equity-based modules, consisting of three Social Emotional Learning modules and four Cultural Consciousness modules…. For instance, as part of the "Elementary and Secondary Social Emotional Learning as it Relates to Racial Injustice" modules, a question stated: "When you witness racism and xenophobia in the classroom, how should you respond?" The two choices listed were: (1) "Address the situation in private after it has passed," or (2) "Address the situation the moment you realize it is happening." When Henderson selected the first choice, she received the following message: "Incorrect! It is imperative adults speak up immediately and address the situation with those involved. Being an anti-racist requires immediate action." To complete the module, Henderson had to select the second choice, which the school district deemed the "correct" answer.

After selecting that option, the following message appeared: "Correct! Being an anti-racist requires immediate action." Henderson disagreed with the "correct" answer because, based on her experience working with students and in special education for over 20 years, it is her view that the response must be tailored to the situation and the student.

The "Cultural Consciousness" modules included a self-assessment checklist. Based on the responses provided by the school district employee, the module calculated a score for how "culturally competent" the employee was. Because Henderson believed the assessment might be reviewed by the school district, she felt compelled to tailor her responses to obtain a higher score, even though some of the answers she gave were inconsistent with her views. In addition, these modules contained a self-assessment reflection and a graphic organizer that asked employees to list their vulnerabilities, strengths, and needs, which Henderson believed would be available for the school district to review. In response to an email Henderson sent to Garcia-Pusateri asking whether the reflection portion of the module was part of the mandatory training, Garcia-Pusateri told Henderson that completion of the reflection questions was required.

Turning to the training session, at one point during the program, Henderson expressed her view that Kyle Rittenhouse was defending himself against rioters and that she believed he had been hired to defend a business. In response, Garcia-Pusateri told Henderson that she was wrong and confused because Rittenhouse "murdered an innocent person" who "was an ally of the Black community."

Subsequently, Henderson did not publicly express her disagreement with statements made by the trainers during the program because she knew that the school district did not accept alternate viewpoints. And if she voiced her true opinions, she would be corrected or considered unprofessional. Henderson feared being written up or terminated from her job if she expressed her true beliefs during the training, explaining: "I felt like we weren't safe to give our opinion or we would be removed from the district." She went on to state that during the training her voice was not heard, and she was told to agree or be seen as disrespectful….

Chief Judge Steven Colloton, joined by Judges James Loken, Lavenski Smith, Bobby Shepherd, and Jane Kelly dissented; a short excerpt (again, you can see more on the factual claims and on the majority's response as to the faculty claims in the full opinion):

A public employee is not injured in a constitutional sense by enduring a two-hour training program with which the employee disagrees. Plaintiffs Henderson and Lumley suffered no tangible harm as a result of the training. They received full pay and professional development credit for attending. They continued in their employment without incident. Lumley earned a promotion soon thereafter…. Both employees spoke up freely in the training and expressed disagreement with the trainers…. The court's theory of "chill" founders in part because the record does not support that the district's directive to "be professional" ever deterred Lumley from speaking….

The majority's conclusion portends a host of litigation over public employee training. If the next "equity training" program proceeds from a color-blind perspective in the tradition of Justice Harlan's famous dissent, and requires trainees to be professional, then the silent employee who favors modern-day diversity, equity, and inclusion will have standing to sue the school district for violations of the First Amendment. Or if a public employer trains its employees about patriotism and the sacred and cherished symbol of the American flag, and requires trainees to be professional, then the silent employee who favors flag burning as a means of protest will have standing to sue the employer for violations of the First Amendment. If it is apparent that the employer considers racial preferences or flag desecration to be unacceptable, then the court authorizes litigation by dissenting employees who claim to have "self-censored" during a training session.

Public employee training will now be fraught with uncertainty. An employer who trains on any subject from any point of view, while requiring employees to be professional, is subject to a federal lawsuit by an employee who disagrees with the training and keeps quiet. Only time will tell how the court elects to manage this new font of litigation. If the court's opinion turns out merely to reflect disapproval of one tendentious training program that judges dislike, then the decision might be good for this day and this ship only. But if the court is true to its word, then the floodgates are open….

Judge Shepherd, joined by Judges Loken and Kelly, also filed a separate dissent.