Scientists Crammed a Computer Into a Robot the Size of a Grain of Salt

Researchers built autonomous robots the size of salt grains—with onboard computers, sensors, and motors that think and swim independently for months.

In brief

- Researchers built grain-of-salt-sized autonomous robots that swim, sense temperature, and operate independently for months.

- The robots use electrical fields instead of moving parts.

- They're the first sub-millimeter robots with integrated computers, costing a penny each to make.

Researchers just shrank autonomous robots down to the size of a speck of dust. And the robots can think—sort of.

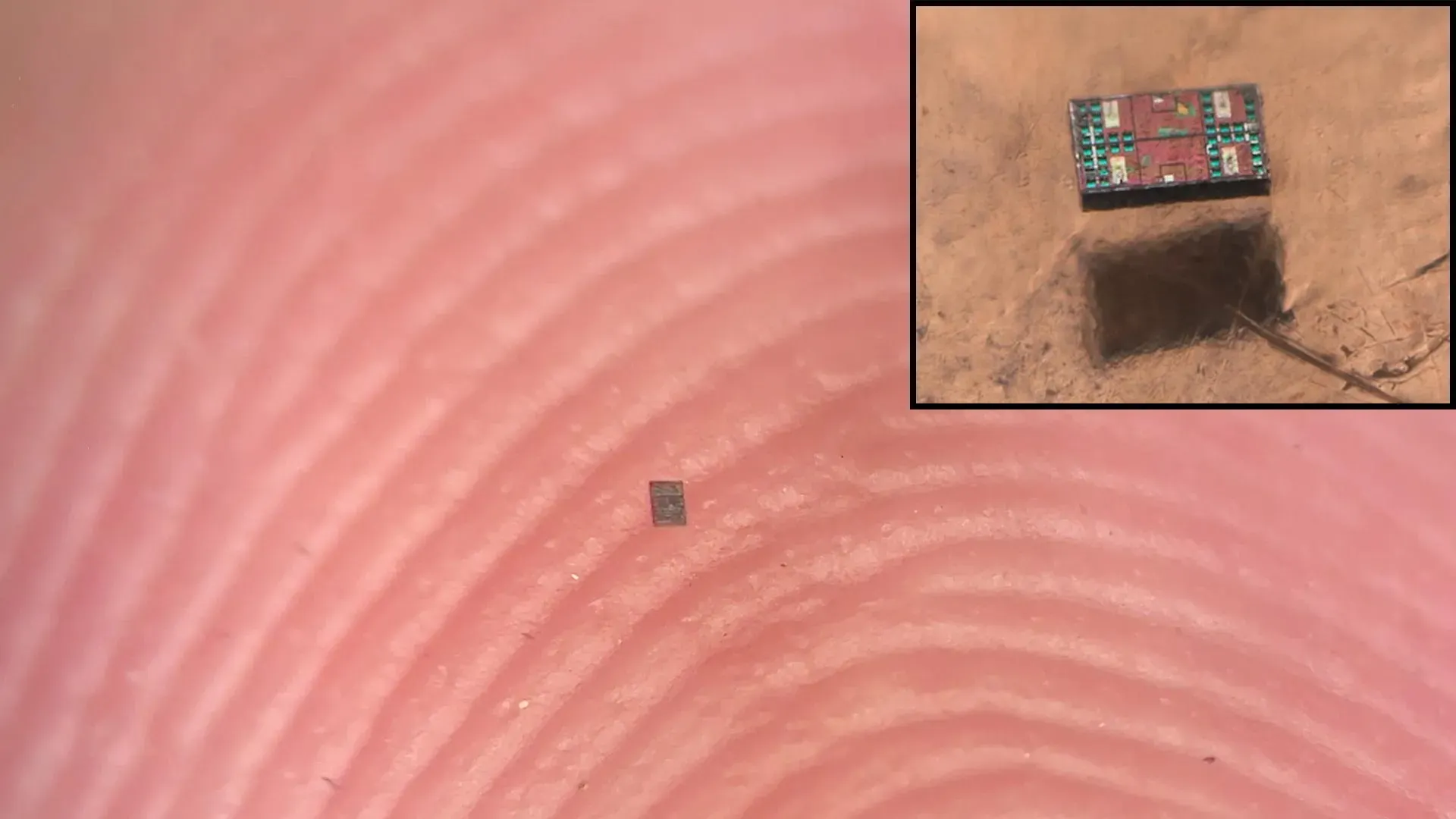

A team from the University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan built microscopic machines—200 by 300 by 50 micrometers, the size of a grain of salt—that swim through liquid, sense temperature changes, make decisions on their own, and operate for months at a time. Each one costs about a penny to produce.

These little robots are fully autonomous. No wires, no magnetic fields, no joystick from the outside. Just a tiny computer, sensors, and a propulsion system crammed into something almost too small to see with the naked eye.

"We've made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller," Marc Miskin, assistant professor at Penn Engineering, told Science Daily. "That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots."

The breakthrough addresses a problem that's stumped robotics for 40 years: how to build machines that operate independently below one millimeter. Electronics kept shrinking, but robots didn't follow. The physics at that scale are brutal—Miskin explained that pushing through water feels like pushing through tar, and tiny arms or legs just break.

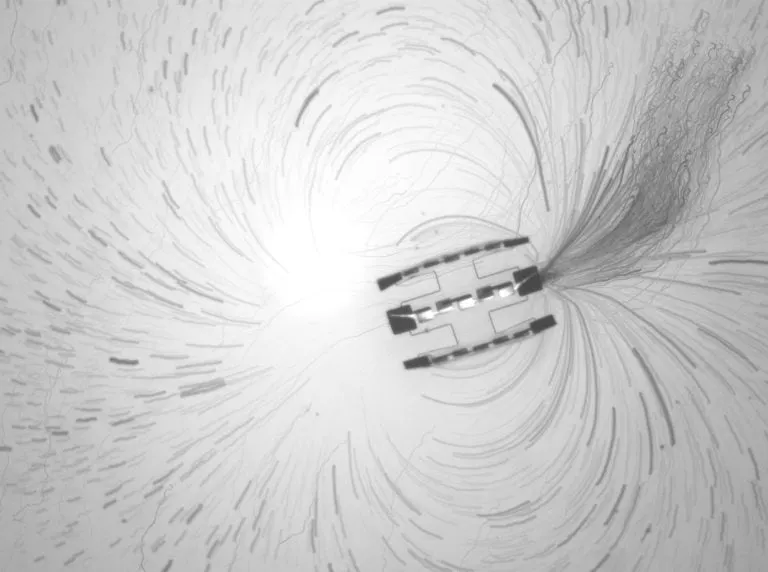

So the team threw out conventional designs entirely. Instead of bending or flexing limbs, these robots generate an electrical field that nudges charged particles in the surrounding liquid. Those ions drag water molecules with them, creating motion.

A projected timelapse of tracer particle trajectories near a robot consisting of three motors tied together. (Credit: Lucas Hanson and William Reinhardt, University of Pennsylvania)

This approach works because it has no moving parts. The electrodes are durable enough to be transferred repeatedly between samples with a micropipette without damage. Powered by LED light, they keep swimming for months.

The tiny solar panels that power these robots produce just 75 nanowatts. To make it work, Michigan designed circuits operating at extremely low voltages, cutting consumption by more than 1,000 times. They also had to completely rethink how software works, condensing what would normally require many instructions into single, specialized commands that fit in microscopic memory.