The psychology behind fraud: Why people fall prey despite knowing better

Representative AI image

It’s easy to judge people who fell for scams. Many times, one simply thinks, “they should have known better”, label them foolish, naive, careless, or ignorant. After all, warnings are everywhere.

Banks keep issuing alerts, digital platforms run awareness campaigns and news regularly reports on the latest frauds and cybercrimes.Yet, when one looks more closely at how scams actually work, fraud is rarely the result of low intelligence or a lack of information. People who are cautious in one context can be disarmingly vulnerable in another. Those who pride themselves on scepticism can make impulsive decisions under pressure.

The question, then, is not why people fail to “know better,” but why knowing better so often fails to protect them.The answer lies not in ignorance, but in psychology.Scams succeed because they are engineered to move past rational judgement rather than confront it. Understanding the psychology behind fraud requires setting aside moral judgement and confronting an uncomfortable truth: vulnerability to scams is not an exception but a human trait. Frauds happen not because people are foolish, but because scammers exploit how people think, react, and cope under emotional stress.

Why even cautious people fall for scams

If knowledge were a substitute for preventing fraud, scams would not be this pervasive. The fact is that some of the most articulate, tech-savvy, and financially educated individuals are duped into cash transfers, sharing credentials, or clicking links that under normal circumstances they never would have trusted.The reason is that scams do not challenge what people know; they manipulate how people feel and think.As Dr Radhika Goyal, PhD (Psychology), said, in her insights shared with TOI , “Scams work by bypassing rational thinking and triggering automatic emotional responses. Even highly educated or careful individuals rely on mental shortcuts in daily life to make quick decisions. Fraudsters design situations that feel urgent, personal, or threatening, pushing the brain into ‘survival mode’.”When this happens, the emotional brain (which reacts fast) overrides the logical brain (which analyses slowly).

In that moment, intelligence offers little protection, because the scam is not engaging logic, it is exploiting trust, fear, or hope.”Dr Medha, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Patna Women’s College (Autonomous), Patna University, situated this vulnerability within a well-established psychological framework, as she talked to TOI.“Even cautious, intelligent, or well-educated individuals can fall victim to scams because fraudulent schemes exploit normal psychological processes rather than ignorance.

From a psychological perspective, scams function by bypassing rational thinking and activating emotional and automatic responses" she said.She further explained this through Kahneman’s Dual-Process Theory.

The psychological biases scammers exploit

Fraudsters do not rely on random manipulation. They repeatedly exploit predictable cognitive biases that guide human behaviour in legitimate social settings.These biases are not flaws, they are mental shortcuts that help people function efficiently in everyday life.

By pretending to be, say, a bank representative, an authority from a government department, an important executive, and short-circuiting the time it takes to reach a decision, scammers tap into compliance ahead of skepticism and reasoning. This insight into behavior is vital, because it helps to re-understand fraud not just as trickery using clever telling, but at its root, an exploitation of psychology, using guilt, fear, and other trigger mechanisms.

Dr Radhika Goyal identified several of the most commonly used psychological levers.

Meanwhile, Dr Medha linked these tactics to foundational psychological theories. Authority-based scams, she notes, draw directly from research on obedience.“Scammers are effective because they take advantage of fundamental psychological theories that explain how humans perceive, decide, and behave in social contexts.

These theories highlight that human decision-making is often guided by automatic, emotional, and socially conditioned processes rather than deliberate reasoning,” she said.Further elaborating on individual behaviour, she added, “Individuals have a strong tendency to comply with perceived authority figures. Scammers exploit this bias by impersonating officials such as bank representatives, police officers, or government agents.

The presence of authority cues—formal language, uniforms, or official symbols—reduces resistance and critical questioning, leading individuals to comply even when requests are unreasonable.

-This has been supported by Milgram’s theory of obedience.”Emotional manipulation, she added, is equally deliberate.“Strong emotions such as fear, hope, guilt, or affection activate the limbic system, which can overpower rational control mechanisms in the prefrontal cortex.

Scammers intentionally evoke emotional reactions to impair logical evaluation and promote impulsive decisions," the assistant professor added, citing Damasio's Affective Decision-Making Theory.Scarcity is another powerful tool.Dr Medha explained how scammers can trigger "scarcity bias" to trap people. Citing Cialdini's Persuasion theory, the professor explained, "Scarcity bias occurs when people assign greater value to opportunities perceived as limited."Scammers exploit this by saying things such as- “Offer valid for 24 hours”, “Only a few slots left”. Another tactic that fraudsters use is "fear of missing out (FOMO)" which "shifts thinking from evaluation to action”, explained the professor.Emotional stress blinds peopleOne of the most troubling aspects of fraud is that victims often recognise warning signs, but only in hindsight. Emotional stress plays a key role in this temporary blindness.“Emotional stress narrows attention. When someone is anxious about money, scared of legal trouble, or feeling lonely, their brain prioritizes relief over verification," said Dr Goyal.Further explaining the psychological mindset of the people under stress, she added, "Under stress, people focus on solving the immediate emotional discomfort — “How do I stop this problem right now?” — instead of asking critical questions."

Red flags may still be visible, but the brain temporarily ignores them because emotional safety feels more urgent than accuracy. This is why scams often target people during vulnerable moments — late at night, after a loss, or during financial uncertainty.

Dr Radhika Goyal, Psychologist

Dr Medha described the same process at the neurological level:

Emotional stress such as fear of loss, financial pressure, or loneliness activates the limbic system, particularly the amygdala, which prioritizes emotional survival responses over careful analysis.

Dr Medha, Assistant Professor, Psychology

Further talking about the stress factor, the professor said, “This heightened emotional arousal weakens the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, reducing logical reasoning, impulse control, and risk evaluation. As a result, individuals rely more on fast, intuitive processing rather than deliberate, analytical thinking, even when warning signs are present.

Stress also narrows attention to emotionally relevant cues, causing people to overlook inconsistencies or red flags that would normally signal fraud.

Consequently, the desire to quickly relieve emotional distress overrides caution, making individuals more vulnerable to deceptive tactics.”

Why victims often stay silent

Even after realizing that they’ve been swindled, victims often opt not to speak out. In most cases, this is not because they lack information or do not care, but due to complex factors involving psychological, social, as well as structural barriers that ultimately favor the fraudsters.Shame and self-blame are some of the deterrents. Victims often internalise responsibility, believing they were “careless” or “gullible,” despite scams being deliberately engineered to exploit normal human trust and authority cues. Admitting the fraud can feel like admitting a personal failure, particularly for educated or financially savvy individuals.

Fear of judgement adds to the reluctance. Victims worry about how family members, employers, or peers will see them, especially when the loss involves large sums or repeated transactions.

In a professional environment, disclosure may be seen as reputationally damaging, reinforcing the instinct to stay quiet.There is also a general feeling that nothing worthwhile will come out of reporting and that what has been lost is irretrievable. This perceived futility discourages reporting, even where formal channels exist.In this context, confusion and intimidation also prevail. Frauds involve tricks and mind games that include numerous platforms, jurisdictions, and phony identities.

Victims often do not know to whom they need to report, what evidence will be required, or fear being dragged into long and stressful investigations. Some are even threatened bluntly by the scammers, further suppressing disclosure.Dr Goyal pointed to shame as a central barrier. “Shame is a major barrier. Victims often blame themselves, thinking, ‘I should have known better.’ This self-blame is intensified by social stigma that equates being scammed with being foolish.”Talking about the feeling of shame leads to isolation, she added, "Fraudsters deliberately reinforce this shame, telling victims to keep the matter confidential or warning them they will ‘get into trouble’ if they speak up. Unfortunately, silence protects the scammer and isolates the victim further. Psychologically, it is easier to stay quiet than to confront embarrassment — even when reporting could prevent harm to others.

”Meanwhile, Dr Medha explained that self-blame is deeply tied to identity. “Victims often internalize the fraud as a personal failure, believing they should have been more careful, which leads to self-blame rather than attributing responsibility to the scammer. Shame triggers avoidance behavior, causing individuals to hide the experience to protect their self-image and social identity.”“Additionally, cognitive dissonance makes it emotionally uncomfortable to admit having been deceived, especially for educated or competent individuals.

Together, shame, damaged self-esteem, and fear of stigma significantly reduce the likelihood of reporting scams, despite the importance of doing so," she added.

Breaking the psychological grip

As scams operate at the emotional, mental level, resisting them requires psychological interruption. In general, fraud succeeds not because the victims are uninformed, but rather because jacked-up emotions temporarily displace rational judgment.

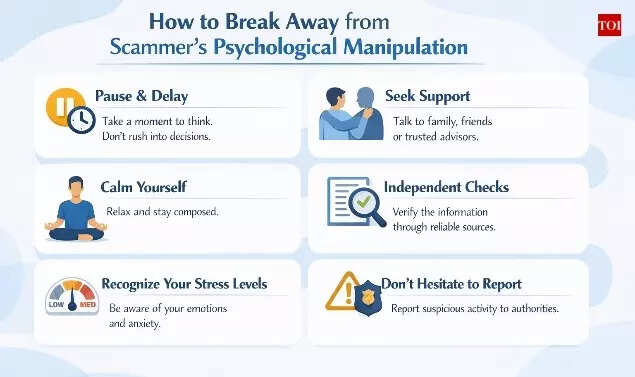

Scammers create a situation that instills urgency, fear, or excitement, forcing fast decisions, narrowing attention, and suppressing doubt. In such a state, one may even fail to notice flagrant red flags. The best counter remains pause: slowing down, stepping away from the communication, or delaying any action, which breaks the emotional momentum on which scams depend.A second opinion is equally important. Bringing in a trusted third party reintroduces perspective and exposes inconsistencies that are hard to see under pressure.

In practice, the strongest defences against fraud are behavioural — time, distance, and verification — rather than just knowledge.Dr Goyal emphasised on simple but effective pauses.

Meanwhile, Dr Medha framed resistance as “mind over manipulation.”"Using Mind Over Manipulation — Scams succeed when emotion outruns reasoning. Breaking a scam requires slowing down emotion, widening perspective, and re-activating rational control," she said.She outlined concrete steps:

A human vulnerability, not a personal failure

The main point to understand in this is that fraud thrives in the space between emotion and reason. It succeeds, not because people lack intelligence, but because they are humans; capable of fear, hope, trust, and urgency. Con artists structure their approach based on these universal characteristics, taking advantage of the instances where the responses are instinctual, meaning where a reaction exceeds the boundaries of logical processing.The susceptibility to a scam is not an anomaly but a side effect of human instincts in pressing circumstances. Recognising this distinction is critical. It shifts the narrative away from personal failure and towards systemic manipulation. When victims understand that they were targeted through deliberate psychological engineering, shame loses its power and reporting becomes more likely. This, in turn, improves visibility into how fraud networks operate and where safeguards fail.The more society moves away from blaming victims and towards understanding the psychology of manipulation, the harder it becomes for fraudsters to win. Awareness framed around human vulnerability encourages openness, earlier intervention, and collective defence; thus, weakening the conditions that allow scams to spread unchecked.