Vera C. Rubin Observatory discovers enormous, record-breaking asteroid in first 7 nights of observations

In its preliminary data release, taken from just seven nights of observations, the powerful Vera C. Rubin Observatory has discovered an enormous, fast-spinning asteroid that sets a new record.

An artist’s illustration of the massive, fast-spinning asteroid 2025 MN45, discovered in the first data from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. (Image credit: NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory/NOIRLab/SLAC/AURA/P. Marenfeld)

Scientists analyzing the first images from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory have discovered the fastest-spinning asteroid in its size class yet.

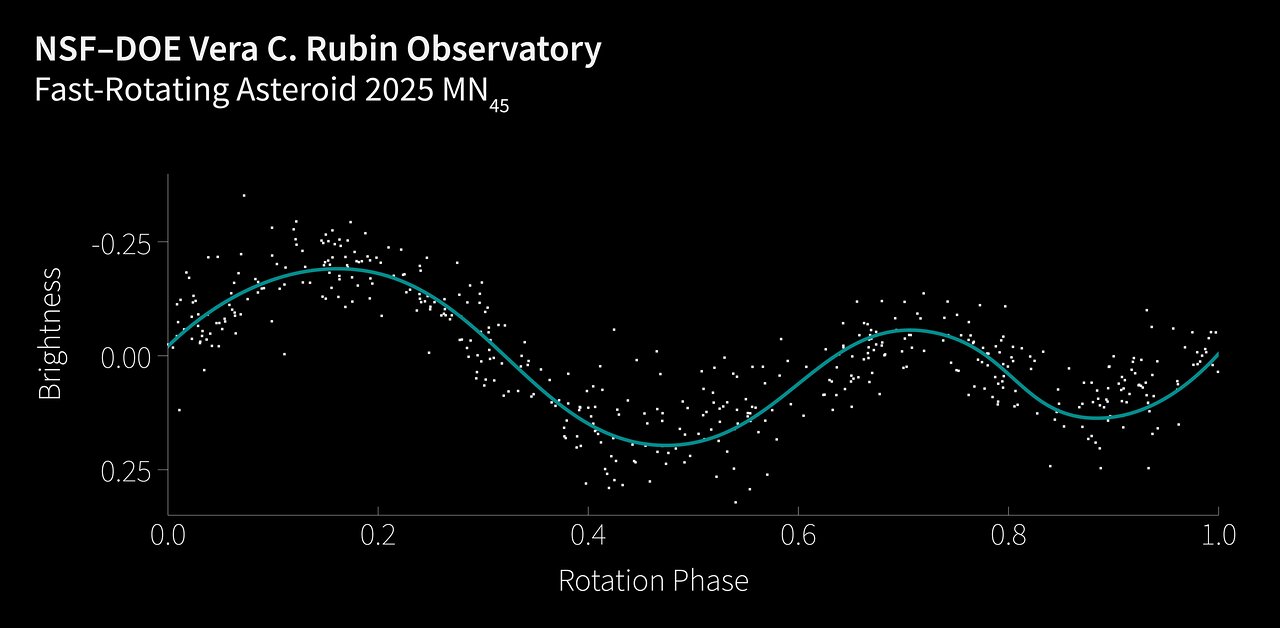

The record-breaking space rock, called 2025 MN45, is larger than most skyscrapers on Earth at about 2,300 feet (710 meters) wide. The massive rock completes a rotation in about 113 seconds — making it the fastest-spinning known asteroid over 1,640 feet (500 meters) in diameter.

The study is the first peer-reviewed paper from the Rubin Observatory's LSST Camera — the largest digital camera in the world — which will repeatedly scan the Southern Hemisphere's night sky over 10 years to create an unprecedented time-lapse movie of the universe.

Rocks that roll

Asteroids are essentially large space rocks, and many are remnants of how our solar system appeared early in its 4.5 billion-year-old history, before the evolution of planets and moons. Therefore, by studying asteroids, scientists can figure out how our solar system changed over the eons.

Scientists found 2025 MN45 using the preliminary data release from the Rubin Observatory, which has already revealed thousands of previously unknown asteroids around the solar system after just seven nights of observations. (The 10-year LSST survey has yet to formally begin, but is expected to start in the next few months.)

The asteroid's remarkably fast spin excited the team, as it provides clues about the ancient rock’s composition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Clearly, this asteroid must be made of material that has very high strength in order to keep it in one piece," Sarah Greenstreet, an assistant astronomer at the National Science Foundation's National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, said in a statement. "It would need a cohesive strength similar to that of solid rock."