What Hew Locke Carries

With his haunting exhibition, Passages, the Guyanese-British artist reminds us that when we survive, so do our ghosts and our wounds.

With his haunting exhibition, Passages, the Guyanese-British artist reminds us that when we survive, so do our ghosts and our wounds.

Hew Locke, "Ambassador 4," detail (2022), mixed media, including resin, metal, MDF, fabric, and plastic; Yale Center for British Art (© Hew Locke, image courtesy John Hammond)

NEW HAVEN, Connecticut — Upon first entering the Yale Center for British Art’s grand lobby, I am confronted by a trio of ships hung on wires suspended from the ceiling. The bows of “The Survivor” (2022), “The Relic” (2022), and “Desire” (2018) all point in the same direction, and all are loaded with cargo, as if they were plucked from the sea mid-journey and shrunken down to fit inside this gallery. They sway slightly on their strings, as though still remembering the rhythm of the water. They are freighted with jute sacks that have rope choking their midsections, potted plants, tied herbal sprigs dangling over the sides, wooden crates marked “fragile,” fishing nets, and other sacks that contain unrevealed supplies. Only two ships have sails, and those are no more than tattered and torn remnants.

Though the hulls of “The Relic” and “The Survivor” were recently painted, most of the vessels’ parts look rusted, corroded, stained, battered by wind and briny water. Still, they resemble models of vessels that could preserve human life. “The Relic” has a two-room bungalow on stilts that’s replete with a staircase, a porch, tilting window shutters, and a corrugated metal roof in wild disrepair. The brochure for Passages, Hew Locke's survey exhibition, indicates that this structure is a replica of a British colonial plantation house. If this work is meant to convey the artist’s experience as a Guyanese expatriate who has witnessed that nation coming into independence, why take this house with you? And why make a house that’s designed to dwell on water?

Installation view of Hew Locke: Passages at the Yale Center for British Art. Left: "The Survivor" (2022); right: "The Relic" (2022) (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

Locke is known for making art that deals incisively and repetitively with the legacies of empire, with its symbols of political, social, legal, and economic power, with the ramifications of nation building to combat the privations of world superpowers. The key code word used to corral all this historical complexity is “colonialism” or “postcolonialism.” I could use the rest of this review to plumb the depths of Locke’s valorous aesthetic and intellectual struggle against a tarnishing and rusting inheritance. But the boats ask me to pose different questions since they seem to carry the artist’s own belongings.

Though he was born in Scotland, Locke’s family originated in Guyana, known as the “land of many waters.” He traveled there by boat, arriving in 1966, and later returned to Scotland via the same means. While in Guyana as a young child he witnessed the colony fight for and declare its independence from Britain. After returning to Britain in 1980, he settled in London.

Installation view of "Souvenir 6 (Princess Alexandra)" (2019), mixed media on antique Parian ware, in Hew Locke: Passages at the Yale Center for British Art (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

The ships' names indicate that they are meant to meld a desire to travel, to be in constant motion, with the drive to survive. But the motion of these ships is simultaneously forward and backward. They bring the past with them in the housing forms they carry, in the sails of “The Survivor” that have images of sugarcane being cut and harvested. There are labor practices, social hierarchies, kinds of punitive violence that repeat in the present (think of the January 6 insurrection) precisely because in our movement toward a postcolonial reality, we hold onto certain habits.

And what else might they bring that I cannot yet perceive, because that cargo is hidden in the holds? Survival cuts in several ways: When we survive, so too do our ghosts and our wounds. More than any other feeling, what occurs to me seeing these vessels is a sense of our precarity, precisely because what I already know about the legacy of colonialism is daunting enough and I am not aware of all the things it makes us — the children of independence fervor and colonial powers — carry.

Beyond the ships, the rest of the show is visually arresting, evoking Locke’s rendering of empire’s signs of authority in his own pidgin language. “Hinterland” (2013) depicts a statue of Queen Victoria that was unveiled in the capital, Georgetown, in 1894, and later banished to a botanical garden during Guyana’s surge toward independence. Surrounding the former queen (whose nose and left arm are missing, excised during the uprisings) are mostly skeletal figures, drawn in outline, who play drums, trumpets, a flute, and banjo as if providing ghoulish musical accompaniment for a macabre dance that is both a celebration and mourning ceremony. The former British monarch, overlaid here with a patterned patina of green and red, looks ghoulish herself, which befits the machinations of a kingdom that managed its colonies through violence.

Installation view of Hew Locke: Passages at the Yale Center for British Art. Foreground: "Jumbie House 1" (2019) (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

The exhibition also includes charcoal drawings portraying the ghostly effigies of monarchy against a backdrop of native Guyanese architecture; prints, with acrylic paint applied, that represent former plantation houses placed on the hulls of boats; and shrunken versions of the actual residences rendered in wood and metal and presented on platforms.

The most beautiful works in the show are those within the three series How Do You Want Me, Natives and Colonials, and Ambassadors. The first set are chromogenic prints that portray Locke in elaborate, maximalist disguise with all sorts of dime-store regalia covering him, as if to make him into his own version of an emperor. Look at “Congo Man” from 2007. It’s a mashup of a soldier holding a long gun, with all manner of bladed weaponry on the floor radiating outward from his feet, but he is festooned with flowers, suggesting the warrior grew from the ground. The statues of Natives and Colonials present the artist intervening in public monuments, remaking them in acrylic paint applied to prints so that they become strange stalkers of the urban landscape, not quite demons, not quite demigods, but something closer to eldritch creatures who no longer belong in our world. This is what “Churchill” (2016) looks like, his towering, resolute figure covered in blue paint with prominent yellow stars. Locke transforms Winston Churchill into a figure who might have arrived on earth from some alien address.

Hew Locke, "Veni, Vidi, Vici (The Queen’s Coat of Arms)" (2004), textile, plastic, oil stick, artificial hair, and plywood (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

Ambassadors are the show’s most terrifying and beguiling works. They consist of warrior figures astride horses, both extravagantly decorated with fabric tatters, medals, bygone currency, skulls, revolvers, and plastic faux gold chains, pearls, and flowers. The figure in “Ambassador 4” (2022), clad in black from head to the horse’s hooves, wears a huge headdress decorated with skeletons who play the same melancholy tune as they do in other works in Passages. She doesn’t seem to represent the end times, but rather the beginning of a future that is dark only because it is shrouded.

Passages is an apt name for the exhibition. The collected work is about transitions, movement, both to and from what we might recognize as our home shores. I can’t tell for sure, but I suspect that part of what Locke is divulging is the secret that we sometimes need to get into a conceptual or material vehicle that can convey us away from our points of origin. If we stay on that transport long enough, we come back to where we started, unless we reach for something beyond this earth, sea, and sky.

Detail of "The Relic" and "The Survivor" in Hew Locke: Passages at the Yale Center for British Art (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

Hew Locke, "Hinterland" (2013), acrylic on chromogenic print (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

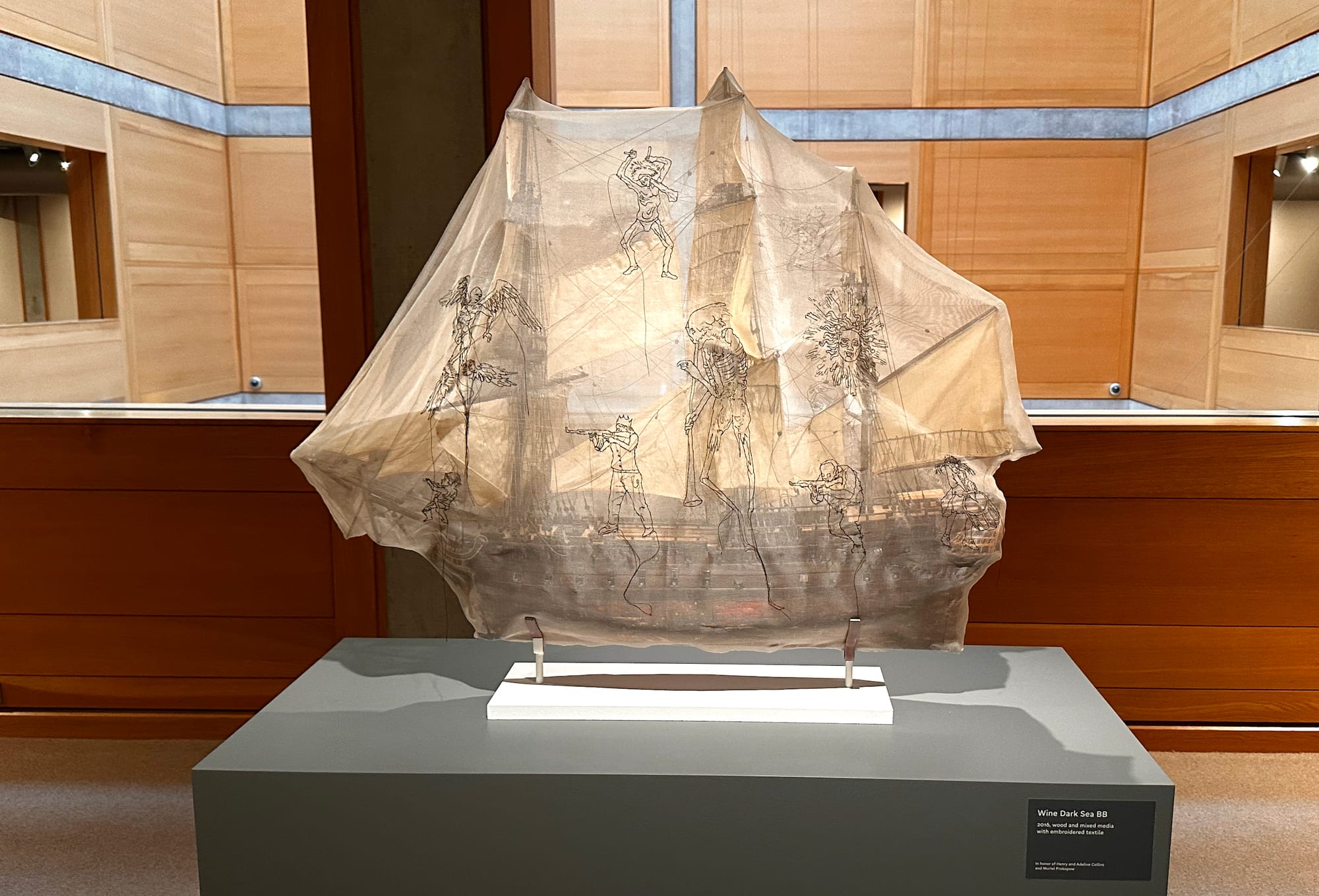

Hew Locke, "Wine Dark Sea BB" (2016), wood and mixed media with embroidered textile (photo Seph Rodney/Hyperallergic)

Hew Locke, "Koh-i-noor" (2005), mixed media on wood base (© Hew Locke, Brooklyn Museum; image courtesy Brooklyn Museum)

Hew Locke: Passages continues at the Yale Center for British Art (1080 Chapel Street, New Haven, Connecticut) through January 11. It was curated by Martina Droth, with Hew Locke and Indra Khanna.