What is the mysterious humming noise in New Mexico that scientists still cannot explain

Residents in Taos, New Mexico, have long reported a mysterious low-frequency hum with no identifiable source. Despite extensive government and university research using advanced monitoring equipment, the sound remains elusive, baffling scientists. Similar unexplained hums have surfaced globally, highlighting the challenges in understanding these persistent, selective auditory phenomena and their potential effects.

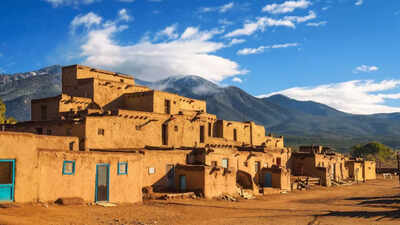

Since the early 1990s, residents in and around Taos, New Mexico, have reported hearing a persistent low-frequency sound with no visible or measurable source. The sound is described as external, geographically bounded, and audible to only a small proportion of the local population.

The issue has been a cause of formal inquiries by government labs and has also attracted quite a bit of research attention in the fields of environmental acoustics and public health. In fact, over the course of the years, various sound monitoring and vibration analysis techniques have been used, but the phenomenon still remains. Comparable reports from other regions have reinforced the relevance of the Taos case within wider debates about sensory perception, environmental exposure, and the limits of conventional measurement in complex sound environments.

What does the Taos Hum sound like

People who report hearing the Taos Hum describe a steady or pulsing sound comparable to a distant engine or industrial machinery operating at low speed. The sound is most often noticed during late-night hours when ambient noise levels fall. It is heard both inside buildings and in open spaces, with no consistent point of origin. A large number of people who experience the phenomenon claim that even if they block their ears or use some kind of hearing protection, the exposure does not change.

In many cases, the noise is described as being accompanied by a feeling of pressure or vibration in the head, chest, or limbs. Reports indicate that the hum is location-specific. Individuals commonly state that the sound weakens or disappears when they leave the region and returns when they come back. These features separate the phenomenon from tinnitus, which is internal and constant regardless of place.

What did researchers record during the Taos study

In response to local concern and political attention, a coordinated investigation took place in the spring of 1993.

The study involved researchers from several United States national laboratories and a university team, working under a public framework intended to address fears of institutional bias. Surveys identified 161 individuals who reported hearing the hum from a population of roughly 8,000. Selected participants recorded the timing of their experiences while researchers carried out continuous monitoring.

Equipment measured acoustic pressure across a wide frequency range, ground vibration, seismic activity, and electromagnetic field strength.

During the monitoring period, participants continued to report hearing the hum. Instruments did not record unusual low frequency sound or vibration levels that matched these reports. Elevated electromagnetic field readings were noted near power distribution infrastructure. Some residents also reported failures or irregular behaviour in household electrical appliances. Several participants attempted to reproduce the sound using electronic signal generators, but no corresponding environmental signal was detected.